Researcher in the Spotlight: Nuno Cernadas

Fresh from successfully defending his PhD, pianist Nuno Cernadas presents his debut album, a deep exploration of Alexander Scriabin’s complete piano sonatas. Trained at top institutions across Europe, including Porto, Budapest, Freiburg, and Karlsruhe, Cernadas has long been fascinated by Scriabin’s visionary music. He is Assistant Piano Professor at the Koninklijk Conservatorium Brussel (KCB) since 2018. His research at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel and KCB, guided by esteemed supervisor Maarten Stragier and Jan Michiels, has culminated in this remarkable recording. In this interview, he shares insights into his artistic journey, his passion for Scriabin, and the challenges of bringing this demanding repertoire to life.

Why did you choose Alexandr Scriabin for your research?

I have continuously played Scriabin throughout my formative years as a piano student. He is a composer to whom I have always dedicated a considerable amount of time and interest. I have always been deeply fascinated by his music, and when I pursued my Master’s degree in Freiburg, I wrote my thesis on his compositions.

My PhD provided an opportunity to delve even deeper and to further specialize in this composer with whom I feel a strong personal affinity, particularly in terms of his musical language and sensibility. There is certainly a personal element to this journey, which has culminated in both my research and my recording.

Why did you specifically choose the ten sonatas of Scriabin for your latest recording?

As a collection, they form the most substantial and meaningful body of work in his oeuvre. They allow us to trace his entire artistic development, showcasing the significant changes and evolution in his compositional style. These ten sonatas span the whole of Scriabin’s creative life. Additionally, they are among the most extraordinary and challenging pieces in the piano repertoire. If I was going to undertake a PhD, I wanted to take on something truly ambitious—something akin to climbing a pianistic Mount Everest.

During your research, you had the opportunity to collaborate with Scriabin experts. What was that experience like?

I was very fortunate to work closely with Håkon Austbø, who recorded the sonatas in the 1990s. He was present throughout my PhD journey as both an artistic supervisor and a jury member. I also invited Maria Lettberg to the jury panel, a Swedish pianist who recorded Scriabin’s complete solo piano works.

It was a great opportunity to have their input, but at the same time, I felt that there was still room in the discography for my own interpretation. Unlike the works of Beethoven or Chopin, Scriabin’s sonatas do not have hundreds of recordings. This gave me the space to bring my own voice to the music. Recording them was a true adventure—recording is never a straightforward process!

Technically speaking, how did you prepare for recording the ten sonatas?

There are many challenges involved. The music is very complex—harmonically and polyphonically. More importantly, you cannot approach Scriabin’s music with a purely grounded, pragmatic mindset. You have to search for meaning, let your imagination roam freely, and explore the perfumes, colours, and vibrations within the sound.

If you play Scriabin too formally, the music becomes dull and loses its essence. Each sonata presents its own unique challenges. The early ones are more traditional, late-Romantic works, so they can be approached in a more conventional manner. However, as you progress, you must develop new approaches—not only in terms of interpretation but also in your touch, technique, pedalling, and even the physical sensation of playing the piano.

Your album features two CDs containing the ten sonatas, along with additional smaller piano pieces. You also chose a specific order for the music. What was your reasoning behind this?

Nothing about the sequencing of these CDs was left to chance. That was one of the exciting aspects of this project. Instead of ordering them chronologically from one to ten, I wanted to present Scriabin’s music in a particular light. The first CD emphasizes the darker aspects of his work, while the second highlights its luminosity and transcendence. This is also reflected in the album’s visual design, which transitions from deep violet and blue to greenish-yellow and orange. In this sense, the recording was an organic result of my research and long artistic engagement with these works.

Did your research also lead you into Scriabin’s mystical and esoteric world, especially in his later works?

Absolutely. To truly understand his music and his creative ideas, it is essential to explore his mystical philosophy. His music is deeply rooted in these mystical concepts.

For example, in the later sonatas, Scriabin’s harmonic language becomes increasingly condensed. Take the Sixth Sonata, for instance—it primarily operates within the octatonic scale. Or consider Prometheus, which is centred around the so-called “mystic chord,” a six-note harmony. The entire piece revolves around this single chord, embodying the idea of synthesis—everything converging toward a single point while simultaneously emanating multiple expressions. This interplay between unity and multiplicity is a well-documented mystical concept, and in this sense, Scriabin’s music is a direct expression of his philosophical beliefs.

I explored this extensively, drawing connections between his music and the Symbolist poetry of his time, as well as the work of painters like Kandinsky. Scriabin was not an eccentric figure; rather, he was deeply influenced by the philosophical trends of his era, just like other artists of his time.

Scriabin even believed that his art could have a tangible impact on reality. In that sense, his ideas were quite radical, weren’t they?

Indeed. For Scriabin, an artistic event was not merely an aesthetic experience—it was an event that could transform reality itself. Taken to its ultimate conclusion, this belief meant that art could bring about a complete transfiguration of the world.

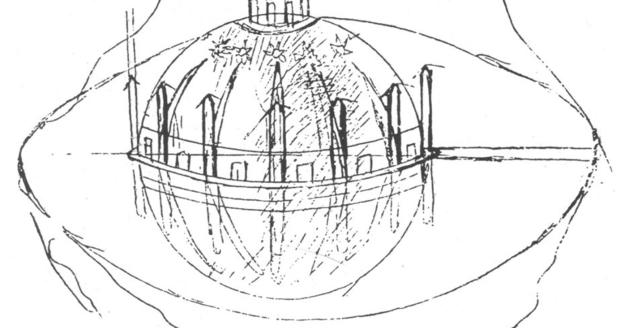

His final ambition was to create a monumental work that would unite all artistic forms—dance, music, poetry—even incorporating scents. He envisioned a grand performance of Mysterium, a piece that would last several days and, through its enactment, would bring about the transfiguration of the world. He saw himself as the one capable of realizing this vision. It was undeniably messianic, but if you view art as action rather than just as object, it begins to make sense.

There is also a common claim that Scriabin was synesthetic—that he could see colours when he heard sounds. What are your thoughts on this?

This is one of the common misconceptions about Scriabin that I challenge in my research. If you compare his statements on colour with scientific studies on synaesthesia, the evidence doesn’t quite align. However, what is certain is that he believed colour should be an integral part of the artistic experience.

He sought to establish correspondences between music and colour in the same way he later attempted with music and dance, or even through the creation of his own artistic language. These were all fundamental elements of his worldview and artistic philosophy. Scriabin was not just a composer; he aspired to be a creator in the fullest sense.

Would you like to learn more about Nuno Cernadas and purchase his latest album?

Reviews

BBC3: This is a very important disc. He [Cernadas] is a terrific pianist, I take my had off.

Musicweb International: I have been very favourably impressed: Cernadas both understands this music and has the technique to play it. He writes his own notes with many interesting ideas about the works. Scriabin enthusiasts who are interested in an alternative to Marc-André Hamelin or Dmitri Alexeev should consider this.

Pizzicato: Cernadas can be delicate and sensual, but he also convinces with original articulation and a pronounced penchant for rubato and dynamic variations. His bold imagination never bores the listener.